How to regulate a converged media universe?

Arlette Meiring

Introduction

At the turn of the century, the transmission of media content was clearly organised. Text was printed in newspapers, magazines and books or posted at the early Internet; audio was communicated through radio or sound carriers such as CDs; and video was broadcast through television. How complex the media environment has become! Nowadays, the morning routine for many involves reading a digital newspaper or checking a news website on a smartphone. For those of us who are not too fond of reading, there is a world full of video clips, podcasts and audio books to watch or listen to while commuting to and from work. After a long day, the smart TV invites us to catch up on our favourite show that was broadcast a few days earlier. And for millennials who do not own a TV, there is the option of video-streaming in bed on a handy-sized laptop.

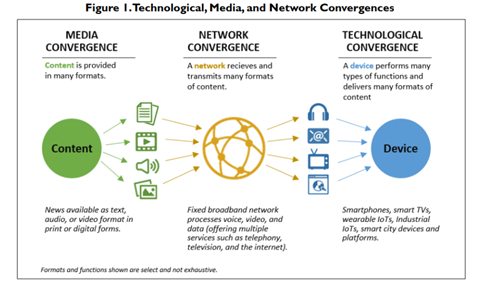

The merging of communication technologies, content, transmission networks, and end-devices is widely known as convergence (see figure I and this infographic).[1] The convergence currently taking place in the media sector is characterised by the increased delivery of media services and content over a single, digital platform: the Internet.[2] Due to digitalisation, different technologies – print, broadcast, Internet – and their respective media services have become ‘decoupled’, meaning that media formats are no longer restricted to one means of transmission and/or device.[3] Boundaries between traditional media industries are slowly blurring towards an ecosystem where, ultimately, “all forms of media are being increasingly stored and transferred in the same format and therefore becoming completely interchangeable”.[4]

Although media convergence is hardly new, European media and communications law is still quite shaped by technological distinctions, with separate regulations for telecommunications, satellite and cable television, radio spectrums and digital services. Of course, the ‘old’ industries of print newspaper publishing, radio and television are still around and may arguably require technology-specific regulation, but the media will likely continue to merge even more than in the past. At some point, regulatory categorisations based on technologies underlying media content may no longer meet their initial objectives. This calls for a longer-term vision of how the law should respond to the ongoing unification of the media environment. Is it time for a reform of media regulation?

Technology-specific regulation

Historically, media industries have been regulated separately according to the technical infrastructures used for the delivery of content. McQuail[5] identified four regulatory regimes that have developed over time and differ in terms of focus and degree of regulation:

- The free press model – the regulation of print media has always been characterised by minimum intervention, not on content but mostly on issues related to ownership and conduct. At a European level, there is no print media specific regulation, but the press must, of course, comply with general rules on privacy and data protection, competition, intellectual property, and other horizontal laws.

- The common carrier model – the regulation of (tele)communications services is also characterised by a low degree of intervention, except with regard to infrastructure and ownership. The EU Electronic Communications Code Directive, which consolidated and updated four previous directives,1 reflects the current European legal framework for the electronic communications sector.

- The broadcasting model – radio and television broadcasting, on the contrary, have always been subject to stringent forms of control, characterised by a focus on the potential harmful effects of content. In Europe, TV broadcasting was long regulated by the Television Without Frontiers Directive (TWFD), which was eventually amended and renamed Audiovisual Media Services Directive (AVMSD) in 2007. In addition, the Satellite and Cable Directives (1999 and 2019) cover copyright-aspects of broadcasting via satellite and cable and of ancillary online services.

- The Internet model – as a relatively new, multi-functional means of content transmission, the Internet has been evolving from an unregulated Wild West to an area of increased regulation. For many years, the E-Commerce Directive (2000) was the only EU instrument specifically aimed at digital services. Later on, this horizontal framework has been complemented with legislation applicable to both offline and online media content, e.g., with regard to copyright, political advertising, the dissemination of child pornography and the dissemination of terrorist content. The foundational framework of the E-Commerce Directive has recently been updated by the Digital Services Act (DSA), a Regulation building on the E-Commerce rules but particularly focusing on issues around online intermediaries.2

Regulatory differentiation between media can be explained by the fact that media have distinct functions, and can also have different effects or impact on media users.

First, media may vary according to their function and, consequently, informational value. The European Court of Human Rights (‘ECtHR’ or ‘the Court’) has frequently recognised the unique capabilities of television broadcasting and of audiovisual media more generally compared to print media, emphasising that “the audiovisual media have a means of conveying through images meanings which the print media are not able to impart” (Jersild v. Denmark, § 31). The Court held, for instance, that television programmes are essential for immigrants to maintain contact with the culture and language of their country of origin to a level that cannot be achieved by foreign newspapers or radio programmes (Khurshid Mustafa and Tarzibachi v. Sweden, § 44-45; text box 1). At the same time, the Court has acknowledged the informational value of the Internet compared to other media because of “its accessibility and its capacity to store and communicate vast amounts of information” (Times Newspapers Ltd (Nos. 1 and 2) v. the United Kingdom, § 27; Ahmet Yildirim v. Turkey, § 48). In other words, the Court has accepted that media are qualitatively different and not always “functionally equivalent”.[6]

Second, media may differ in terms of effect or impact on people’s perceptions. A recurring phrase in the ECtHR’s case law is the “immediate and powerful effect of the broadcast media” compared to print media and Internet-based media (Jersild, § 31). The potency of television broadcasting is that it leaves media users without control: once you turn the TV on, it starts showing you audiovisual content without a warning (which, as previously noted, can already be powerful as such). According to the Court, other media content does not have the same “synchronicity” as broadcast information (Animal Defenders International v. the United Kingdom, § 119). For a long time, the inherent impact of television has further been “reinforced” by the fact that for many households, the medium was “a familiar source[s] of entertainment in the intimacy of the home” (ibid.). Whether this is as apparent today as it was at the time of the Animal Defenders-judgment in 2013 is highly debatable, particularly in view of the decline in radio and television audiences worldwide. This does not change the fact, however, that television programmes are still broadcast widely and thus continue to shape the (pluralistic) media landscape (Informationsverein Lentia and Others v. Austria, § 38). Against this background, the Court held that “a [regulatory] distinction based on the particular influence of the broadcast media” can be considered “coherent” (Animal Defenders International v. the United Kingdom, § 119).

In a similar vein, the Court has recognised the special impact of Internet-based media compared to print media. In a case concerning a news article that had been published in a printed newspaper as well as on the newspaper publisher’s website, the Court observed that “the Internet is an information and communication tool particularly distinct from the printed media, especially as regards the capacity to store and transmit information”. Considering that the Internet is “serving billions of users worldwide” and that it “is not and potentially will never be subject to the same regulations and control”, the Court found that “the risk of harm posed by content and communications on the Internet (…) is certainly higher than that posed by the press”. It therefore accepted that there could be a need for different policies governing reproduction of material from the printed media and the Internet (see Editorial Board of Pravoye Delo and Shtekel v. Ukraine, § 63 (2011); see also Węgrzynowski and Smolczewski v. Poland, § 58 (2013).

It is important to realise that the perceived heterogeneity between media in terms of functionality and effects can often be attributed to the technologies providing access to media services and their content. As noted, television imagery is deemed impactful because it is technically capable of beaming moving images directly into the intimacy of the living room, without giving people a choice to select particular content beforehand. And because of the Internet’s inherent global connectivity and accessibility, an offensive online publication may cause more harm on a bigger scale than an offline publication in a local or national printed newspaper. The Court has slowly started to acknowledge the power and influence of online media, stating, for example, that it “does not rule out that certain online operators – such as major platforms with national or international reach and/or hosting large volume of third-party content – may present specific challenges for the integrity of electoral processes” (OOO Inforationnoye Agentstvo Tambov-Inform v. Russia, §89). Thus, in cases where technology demonstrably leads to increased functionality and/or impact, technology-specific regulation can be justified.

Text box 1: Functional equivalence between media cannot be assumed

In the case of Khurshid Mustafa and Tarzibachi v. Sweden (§ 45), the ECtHR found that television broadcasts “cannot be equated” with newspapers and radio programmes. Immigrants from Iraqi origin living in Sweden had been ordered by their landlord to take down the satellite dish they had been using to receive television programmes from Iraq. The Court considered that although the tenants “might have been able to obtain certain news through foreign newspapers and radio programmes, (…) these sources of information only cover parts of what is available via television broadcasts.” The Court pointed out that some television programmes were broadcast in the immigrants’ first language. They could provide the family not only with political and social news from their native region, but also with cultural expressions and entertainment that could help them maintain contact with the culture and language of their country of origin (§ 44). It is implied in the Court’s considerations that (foreign) newspapers and radio programmes are inherently limited in providing effective informational opportunities for particular groups of people in society and are therefore not functionally equivalent to television broadcasts.

Text box 2: Different effects or impact on the public

In the case of Animal Defenders International v. the United Kingdom (§ 119), a non-governmental animal rights organisation wanted to broadcast a 20-second television advertisement as part of a campaign regarding the treatment of primates. The advertisement was refused by the UK Broadcast Advertising Clearance Centre on the basis of the statutory prohibition on political advertising on radio and television. The NGO claimed, amongst other things, that “limiting the prohibition to radio and television was illogical given the comparative potency of newer media such as the internet”. The Court did not follow this reasoning, considering that “a distinction based on the particular influence of the broadcast media” was “coherent” given the “immediate and powerful impact of the broadcast media” and that information on the Internet and social media “does not have the same synchronicity or impact as broadcasted information”.

Technology-neutral regulation

However, the question is whether the assumption that some media are more impactful or influential than others – due to their technological features – can still be maintained in an increasingly converging media environment where “we use different media in ways that are alternately interchangeable and complementary”.[7] In 2013, the Court still refused to accept that there had been “a serious shift in the respective influences of the new and broadcast media”, implying that, at the time, there was still “a need for special measures for the latter” (Animal Defenders International v. the United Kingdom, § 119). But as the introduction to this blogpost illustrates, the present-day dissemination and consumption of media content is no longer tied to specific channels. Many offline media industries have created ‘digital twins’ of their services: traditional broadcasters, for instance, increasingly operate online via video-on-demand platforms, and newspaper publishers manage websites, YouTube channels and online podcasts. As both existing and new media continue to evolve into digital services, ultimately there will no longer be a reason to regulate on the basis of technological criteria.

What is the best way to regulate a converged media environment? In its recent Internet case law, the ECtHR has taken an approach of what in literature is referred to as “adaptive replication”, that is, the replication (or: translation, modernisation) of traditional principles and objectives of media regulation in respect of the Internet, but in a way that is adaptive to the distinctive features of the new technology era.[8] This approach has provided the ECtHR both guidance and flexibility. At the same time, one may wonder whether the media ecosystem has reached a point where bigger rethinking is necessary, perhaps in the form of a new legislative framework applicable to both digital and analogue media, regardless of their technological features.

The main argument for technology-neutral regulation is that, in the end, it is the effects of technologies that should be regulated, not the technologies themselves.[9] Look at it this way: on its own, a television is “nothing but wires and lights in a box”, or, as some have imaginatively called it, “just a toaster with pictures”. Wires, lights and toasters do not influence public opinion, but the editorial content delivered through the wires, does. It could therefore be argued that it is the content that should matter most, and not the fact that that content is being transmitted through radio waves, cable networks or satellites, or accessed through a television, laptop or smartphone.

Besides these normative considerations, there are also practical benefits associated with technology-neutral regulation (notably, not limited to the media-sector). First, technology-neutral law making is generally more sustainable. Since rules do not have to be adapted to new technological developments, the ever-recurring problem of ‘the law lagging behind technology’ can be circumvented. Second, technology-neutral law making is considered easier for legislators who have a limited understanding of different technologies and the most appropriate standards. Technological neutrality saves time and expert opinions, and reduces the risk of adopting inferior standards that might hinder the development of new tools and technologies. Third, technology-neutral legislation eliminates the risk of discrimination and unfair competitive advantages for certain technologies. Since the same services are treated equally, no method or technology of delivery will be favoured over the other. And last, technology-neutral laws provide flexibility for market actors to perform legal duties in a way that works best for them, thereby allowing for development and innovation.[10] This does not mean, by the way, that regulators are powerless against potential harmful innovations: developers of new technologies must still comply with the general aims and prescriptions of the law (see text box 3).

Overall, it could be argued that media regulation based on the principle of technological neutrality is best suited for the digital age.

Text box 3: Technology-neutral regulation of media: drawing lessons from the financial sector?

In the financial sector, regulators have embraced the idea of technology-neutral regulation and have developed a mechanism of the so-called ‘regulatory sandbox’.[11] The main idea behind this mechanism is to set up a framework in which start-ups and existing market players may experiment with new (financial) products. Instead of prohibiting innovative technologies that do not fall within the scope of existing regulation and do not fulfil the necessary legal requirements, the supervising authority overseeing the sandbox must ensure that the products are compatible with the general aims of the law. After some time, the supervising authority will decide whether it is desirable to continue the arrangement or suspend the products that it thinks are too harmful until the legislator has put in place new rules.[12] The sandbox-model allows regulators to stay on top of new technologies without unduly burdening innovators with excessively detailed or outdated requirements.

Technology-neutral media regulation in the European Union: audiovisual media

As was observed long ago and still holds true for today, the delivery of audiovisual content is “at the heart of the convergence process”, and consequently, “at the heart of current regulatory debates around convergence.”[13] In 1989, when the European Union enacted the Television Without Frontiers Directive (TWFD), the audiovisual media landscape was limited to television. Ever since, the Directive has been revised twice to respond to ongoing media convergence by including newly emerged online services into its scope, i.e., video-on-demand services (2007) and video-sharing platform services (2018). Although online audiovisual content services were already regulated by the E-Commerce Directive – and now, the Digital Services Act (DSA) – in their capacity as ‘information society services’, the introduction of sector-specific rules was deemed necessary to ensure a level playing field for services competing for the same audiences and revenues.[14]

During the 2007 revision, the EU fundamentally changed its approach to identifying audiovisual media services, shifting from a “technology-based approach” to “an approach based on the use of media”. The TWFD was renamed Audiovisual Media Services Directive (AVMSD) and was declared applicable to “all audiovisual media services” regardless of their mode of delivery (Article 2(1) AVMSD). Since the introduction of a Chapter on Internet-based video-sharing platform services in 2018, the modern EU audiovisual media landscape has been captured by one single regulatory framework.

However, it could be argued that the EU legislator has yet not fully committed to the idea of technological neutrality in the AVMSD. Even after multiple revisions, the Directive still contains a few strict provisions in the area of advertising that apply to television broadcasts but do not apply to online audiovisual media services. This essentially technology-based distinction, which has been referred to as ‘graduated regulation’, once emerged from the perceived choice and control a viewer can exercise with regard to on-demand services as opposed to television broadcasting (recital 58). Admittedly, the distinction was further downplayed during the latest revision of 2018, by an increase in the regulation of on-demand services, but it is still present. Several authors argue that by (even mildly) adhering to the approach of graduated regulation, the principle of technological neutrality is effectively abandoned.[15]

Conclusion

As the ECtHR-approach of “adaptive replication” and the development of EU audiovisual media regulation illustrate, European media law is moving slowly on the continuum from ‘full technological specificity’, on the one end, to ‘full technology neutrality’ on the other, thereby responding to a media environment that is rapidly changing but not yet fully converged. As long as technological differences could still (significantly) affect the respective functions and impact of media services on users, a certain degree of differentiated media regulation based on technological features can be justified. Nevertheless, regulators must stay on top of technological developments and keep their eye on what is important: the content and effects of media. The moment technology stops being a useful proxy for impact or effects, the technology-specific approach must be abandoned and a comprehensive approach to media should be adopted.

References

[1] S.E. Park, ‘Technological Convergence: Regulatory, Digital Privacy, and Data Security Issues’, US Congressional Research Service, 30 May 2019.

[2] S. McPhillips and O. Merlo, ‘Media convergence and the evolving media business model: an overview and strategic opportunities’, The Marketing Review, Vol. 8, No. 3, 2008, p. 237.

[3] C. Peil and S. Sparviero, Media Convergence Meets Deconvergence. Global Transformations in Media and Communications Research – A Palgrave and IAMCR Series, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017, p. 4

[4] V. Miller, Understanding digital culture, London: SAGE Publications, 2011, p. 73.

[5] D. McQuail, ‘Media, Regulation of’, in: G. Ritzer (ed.), The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology, Blackwell Publishing: Malden 2007, p. 2912-2915.

[6] T. McGonagle, ‘The Council of Europe’s standards on access to the media for minorities: A tale of near misses and staggered successes’, in M. Amos, J. Harrison and L. Woods (eds.), Freedom of Expression and the Media, Leiden/Boston: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2012, p. 123-124.

[7] T. McGonagle, Case Note to ECHR 18 May 2021, App. No. 43351/12 (OOO Informationnoye Agentstvo Tambov-Inform v. Russia).

[8] T. McGonagle, ‘Free Expression and Internet Intermediaries: The Changing Geometry of European Regulation’, in: Frosio, G. (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Online Intermediary Liability, Oxford University Press, pp. 467-485. See also K. Jakubowicz, A New Notion of Media [video, 8:57 and further].

[9] B.J. Koops, ‘Should ICT Regulation be Technology-Neutral?’, in: Starting points for ICT Regulation, Deconstructing Prevalent Policy One-Liners, IT & Law Series Vol. 9, The Hague: T.M.C. Asser Press 2006, section 4.3.5, B.1, B2.

[10] E. Puhakainen and K. Värynen, ‘The Benefits and Challenges of Technology Neutral Regulation – A Scoping Review’, Conference Paper for the Twenty-fifth Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems, Dubai, UAE, 2021.

[11] M. D. Fenwick, W. A. Kaal, and E. P. M. Vermeulen, ‘Regulation Tomorrow; What Happens When Technology is Faster than Law’, American University Business Law Review 2017/6 issue 3 p. 561-594, p. 591-593; see also D. Ahern, ‘Regulatory Lag, Regulatory Friction and Regulatory Transition as FinTech Disenablers: Calibrating an EU Response to the Regulatory Sandbox Phenomenon’, European Business Organisation Law Review 2021/22 p. 395-432.

[12] E.g., the sandbox of the Dutch financial authority.

[13] M. Ariño, ‘Content Regulation and New Media: A Case Study of Online Video Portals’, Communications & Strategies, Ofcom: London, No. 66, 2nd quarter 2007, p. 115.

[14] Directive 2010/13/EU, recital 10-11; Directive 2018/1808, recital 4.

[15] See also E. Símon, ‘New Media legislation: Methods of Implementing Rules Relating to On-Demand Services’, in: B. Klimkiewicz (ed.), Media Freedom and Pluralism: Media Policy Challenges in the Enlarged Europe, Budapest: Central European University Press 2010, Section 4.2; and see A. Celsing, ‘Dealing with Change: Impact of Convergence on European Union Media Policy’, in: S.J. Drucker and G. Gumperts, Regulating Convergence, New York: 2010, p. 52.

1. The Access Directive (2002/19/EC), the Authorisation Directive (2002/20/EC), the Framework Directive (2002/21/EC) and the Universal Service Directive (2002/22/EC).

2. At the time of writing of this blogpost, a political agreement on the DSA between the European Parliament and Council (April 2022) was reached (formal approval soon expected).